EXHIBITIONFire and Rain

Fire and Rain tells a story of loss and the rebirth of hope.

Zela Bissett’s body of work Fire and Rain formed part of a joint exhibition entitled Paper, with fellow artist Heather Matthew at Beaudesert Regional Gallery running from February until March 2023.

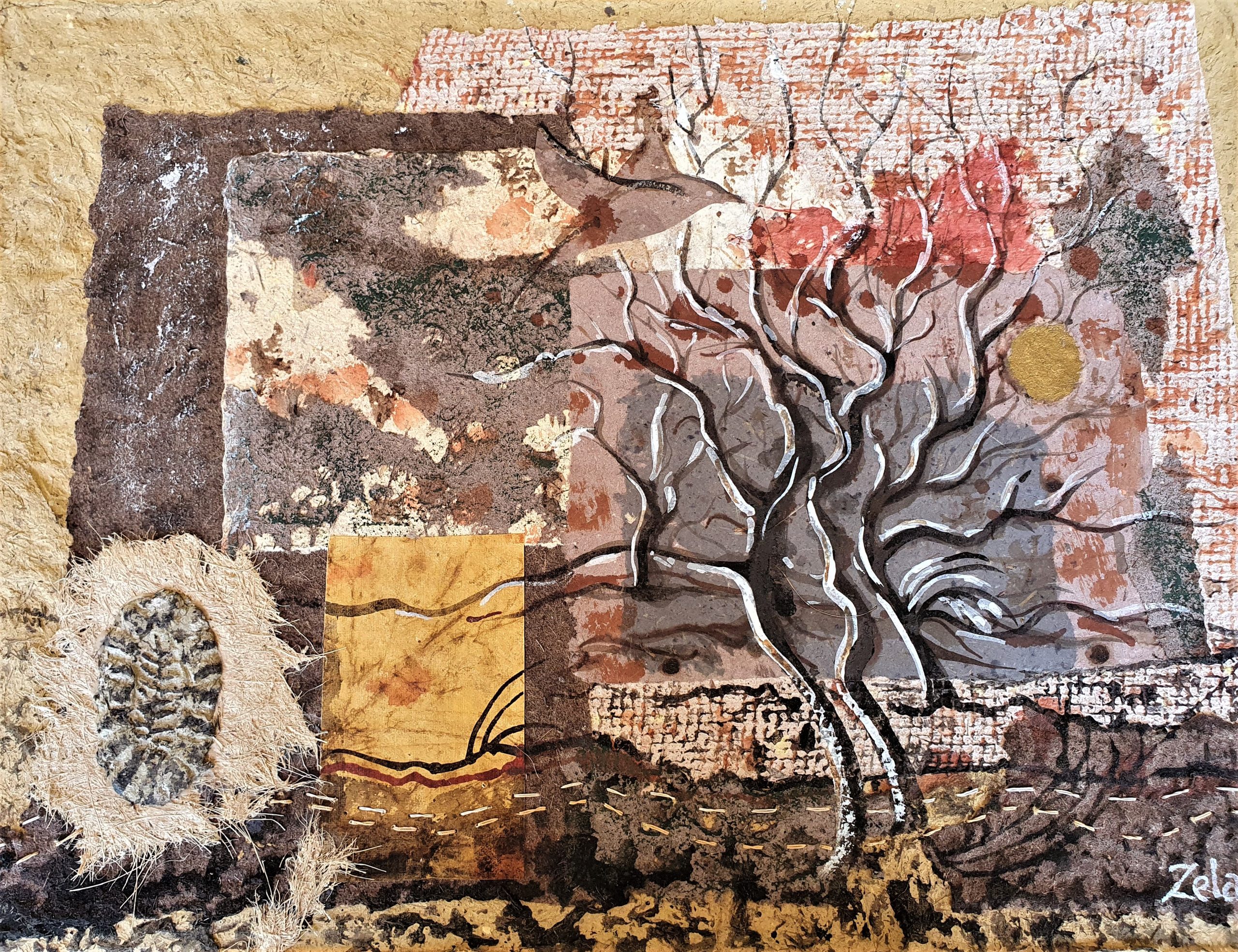

In re-imagining a better future and I actively explore ways of creating artworks from natural sources, using environmentally friendly processes and generating no waste that is not safe for my own garden. For example, I make paper from plants I grow, or those available freely, or weeds whose removal benefits the native bushland. I use natural materials such as berries and bark to make inks. I also harvest weed vines or spent garden plants to make twine by hand twisting. In my work I reimagine some of the possibilities of a more just and environmentally friendly future, by making make works not just on nature-friendly themes, but from materials which nature freely offers.

In my backyard studio, I take plants harvested seasonally from my permaculture garden and cook them to yield cellulose which I make into paper. For decoration, often fragments, petals and tendrils are embedded directly onto the watersheet (still-wet paper). I strive to use a minimum of commercially manufactured ingredients, sourcing colours through ochres and earth minerals where possible. My works are therefore restrained in colour palette to relatively subtle earthy tones, although over two decades of experimentation I have amassed a range of colours which I use in assemblages/collages to create works complemented by charcoal, ochres, chalks and inks/pigments brewed from local plants. Works are often them overstitched or otherwise finished by hand with twine formed from local plants (often weeds). My themes are associated with caring for the earth and celebrating nature. They encourage the reimagining of a sustainable future.

Fire and Rain concerns the impacts of extreme weather on a place very close to my heart on Butchulla country, K’gari, the beautiful island listed as part of the whole world’s heritage by the United Nations. 100 year ago she was given another name – Fraser Island after a group of castaways who washed up on her shores. K’gari was a place of joy and plenty for the Butchulla people until then, but after colonisation became a place of sadness, massacre and exile. Thanks to the efforts of local people, in particular a man named John Sinclair, K’gari was spared the worst ravages sand of mining in the 1970s. John Sinclair next turned his efforts to stopping logging, which proved to be a longer battle. Giant trees on fragile coffee rock called Pibin, (Syncarpia hillii or Fraser Island satinay), were found to be resistant to marine borers and many millions of superfeet were cut from K’gari and shipped all around the world to be used in projects including the construction of the Suez Canal.

After mining and logging ceased and K’gari was given World Heritage listing, beautiful photos of her tall forests, cool creeks, shining Sands, her deep crystal-clear lakes were circulated all around the world and proved attractive to many tourists. By current figures almost half a million people visit K’gari every year. Some of these people love K’gari and care for her tenderly, but among the visitors are also people who think that to go to an island out of the public eye means you can do whatever you like. In 2020 a group of five young men trekked off into the north of the Island. They lit a fire in an area with a heavy fuel load in very hot conditions. After kicking sand over it they went their way. Soon the radiant heat from the fire ignited the leaves and branches nearby and before the authorities knew about it, fire began to consume the vegetation of the island. Local residents and Butchulla people (who haven’t been allowed to live on the island for generations) put their very lives on the line to put that fire out. For 6 weeks it burned something until one-third of K’gari s vegetation had turned to smoke and cinders. Due to a huge effort, the villages of Eurong, Happy Valley and Orchid Beach were saved and so were the tall forests of Pile valley.

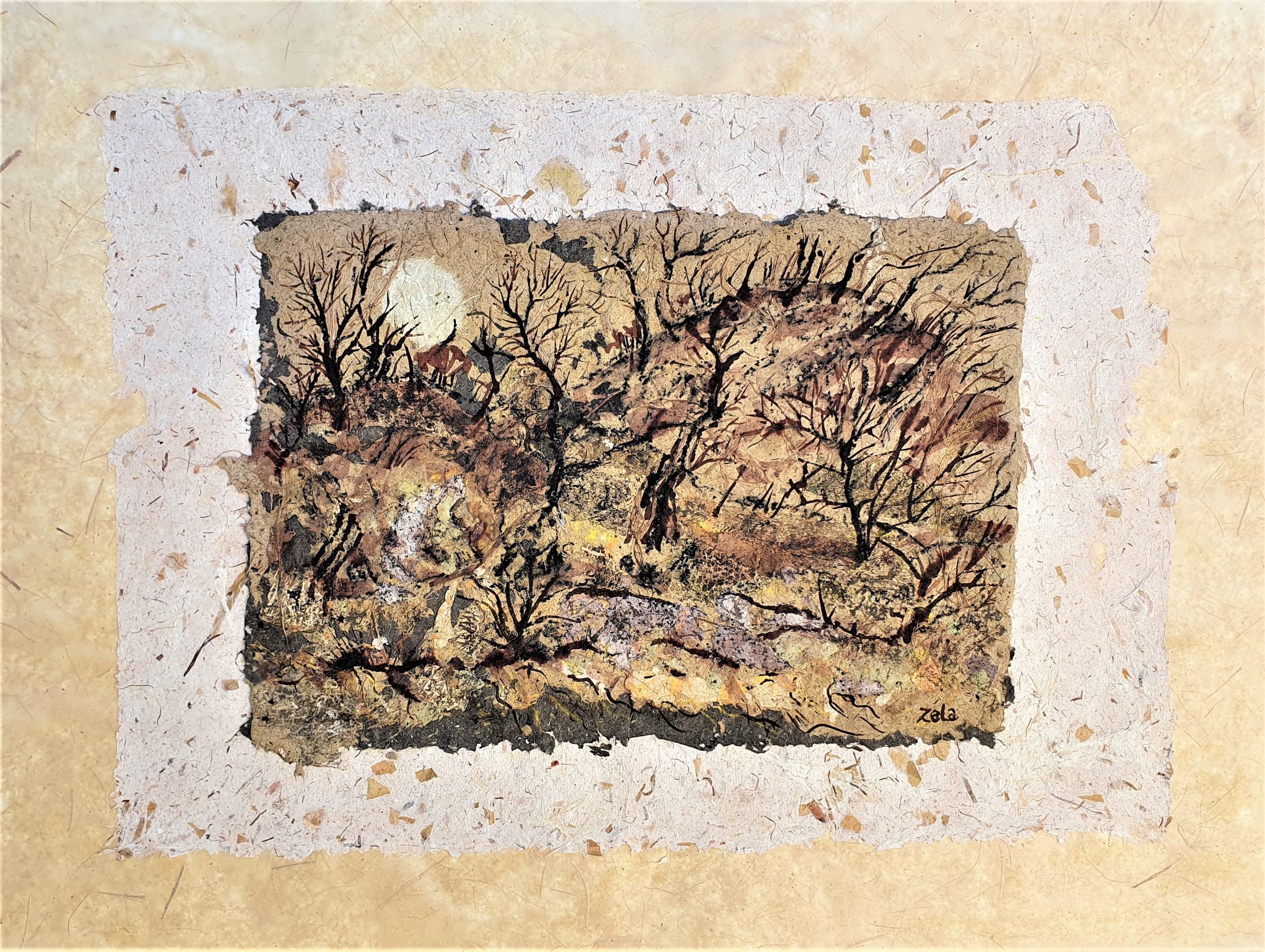

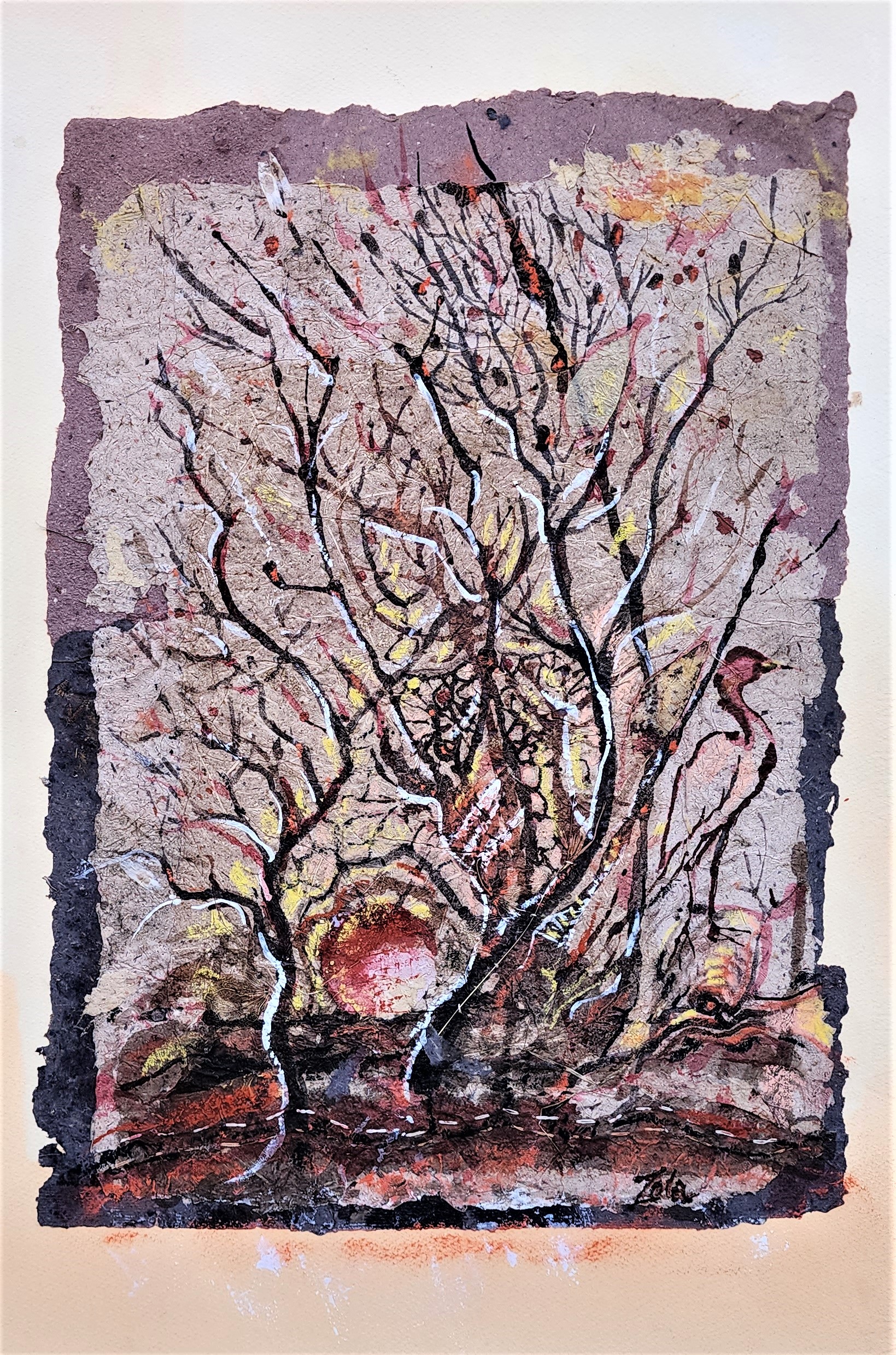

For many weeks I could not overcome feelings of pain, sadness and a taste of ash in my mouth. During that period I made the Firestorm series of works, using papers made from local plants, earths, burnt bark and charcoal collected from burned sections of the Cooloola (mainland) side of the sandmass.

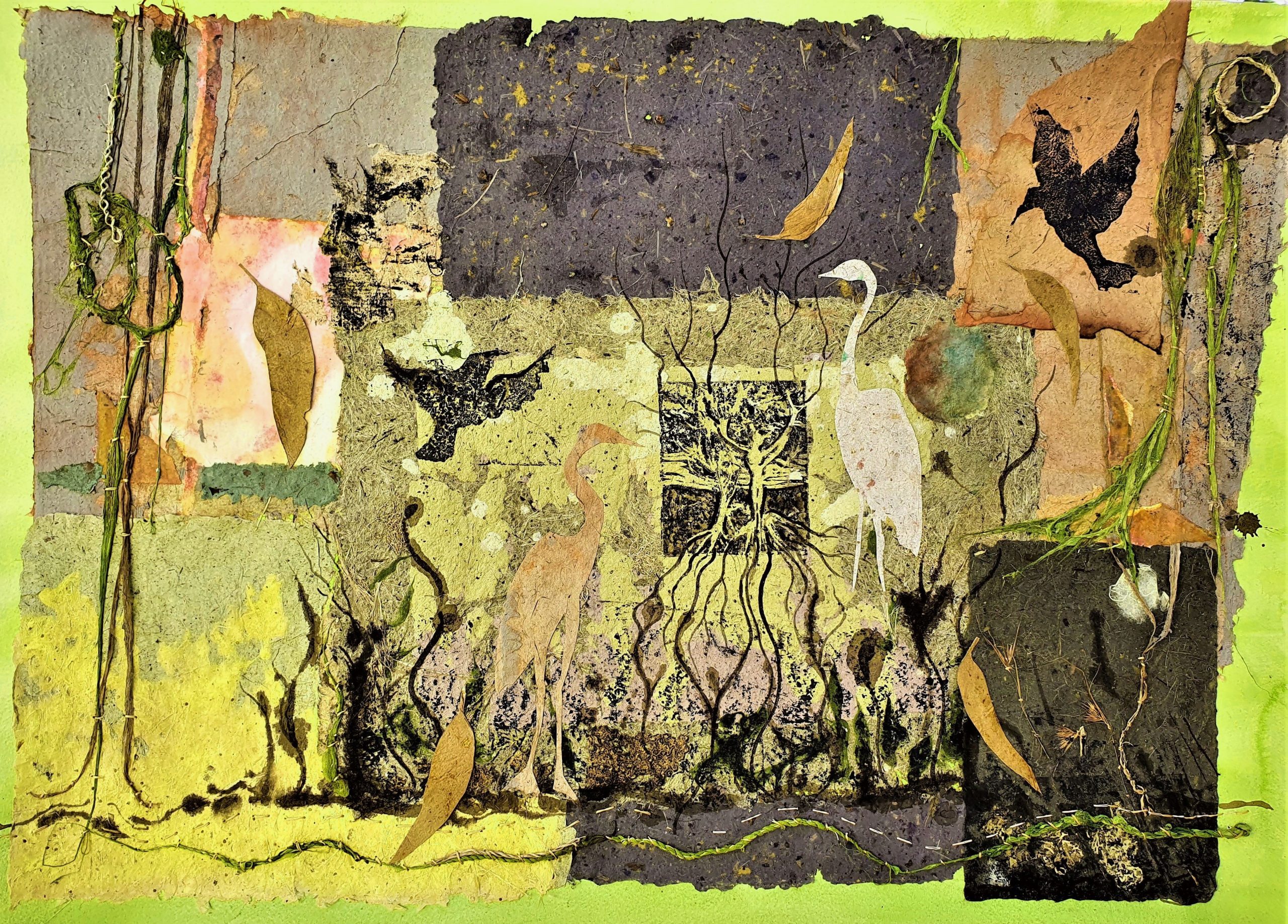

It seemed that the desolation might last indefinitely until one night the temperature dropped. Gusty winds sprang up and brought a new scent of dampness to the air. As I lay with wakeful a deep rumble was heard from the mountains. Big drops of rain began to fall on the tin roof. As it blew cool damp breeze through the house, I felt my despair finally lift. The thud of rain grew heavier until it was a roar and I found myself smiling with the return of hope. As soon as dawn lit the sky I literally ran up to my studio and started on the work that had taken shape in my mind – The Rain Garden. Dragging out my last sheet of large archival paper I began to collage using all the elements of hope and growth, papers made from garden plants, twine hand twisted from pond algae, fragments of leaf and tendril. During the following months, I created works of rebirth and recovery and felt that I was in partnership with all the creative forces helping to repair K’gari: the residents building water tanks, the volunteers collecting seed and germinating it, the rangers planting new trees, the birds building new nests and the wily wan’gari (dingo) mothers giving birth in the thickets. For the following months, I worked to make works that celebrated the return to life and health of the post fire world. As though serving the creator gods, like the original K’gari, I poured my powers into artworks which envisaged the healing of the ravaged land.